…or how to fit the whole learning subject of one class into a half a dozen tweets.

Who loves exam preparation? Be honest! It’s always the same: last-minute learning stress. I accepted that fact and developed a learning technique exactly for that. With this method, you can procrastinate learning until the day before the last lesson. If you have just two weeks left until the exam: That’s plenty enough time! It even works for having only one week before the examination without any last efforts.

During my studies, I mainly used three learning techniques for achieving high marks. This is the one I used for very boring stuff (e. g. learning PowerPoint slides by heart). As far as I know, this technique hasn’t been invented yet. I claim to be the first one that found it :-). So here I present to you – for the first time in the history of mankind: “Extreme Reduction.”

History of invention

I was over 30 when I pursued my master’s degree in information management. I had some fear that my brain was too old for all that studying stuff. I thought that my free space in my memory was very “fragmented” like a hard disk and almost full. So I spent a good part of my time searching for the optimal learning technique.

Among other things, I also asked my wife about it. She had done her Bachelor’s degree in Economics while she was pregnant and raised up our first child. She told me that she had to learn a lot of useless stuff in a short time. In the exam, she had to “puke” all the knowledge from her brain upon paper. The knowledge was gone afterward. She “learned” by simply writing off the learning matter over and over again until she knew it by heart. She said that this “brainless activity” help her to get her high marks. Ridiculous! But well, it worked!

I thought that “methodology” would work for me, too, for three reasons: I can write very fast, and I’m kind of lazy thriving towards the maximal result with the least amount of effort, so brainlessly writing something off, again and again, fits my learning strategy. And I wanted to forget about all the learned stuff as soon as possible to make room for other stuff that I had to learn. I started my first learning approach by just writing off the first few PowerPoint slides of my subject of study. But I quickly discovered the limit of this method: It was simply too much content I had to write off. The idea of Extreme Reduction was born.

Basics

Extreme Reduction is a learning technique that reduces the amount of content of the subject of matter from long texts to short acronyms. With Extreme Reduction you will repeat your learning subject at least seven times with the following steps:

- Listen: Pay attention in class.

- Read: Read through the learning matter to get a feeling for it.

- Excerpt: Write down the core message from sentences and listings

- Normalize: Create consistent, linear content

- Write off: Write the normalized version off (one or many times)

- Abbreviate: Cut down listings to acronyms

- Learn by heart: Decode the abbreviated content again and again

The key is to reduce the amount of learning matter radically. Then we only write off the shortened version of it. This is very efficient because we don’t need to bother with the entirely content of the course. This makes it very easy to repeat and therefore memorize the learning material. Speaking in technology terms: We compress all the data we need to know in nice little files and place them on our hard disk. Then we memorize only the memory addresses/references to the files. We are now able to iterate through the addresses at extreme speed and load the full data if necessary.

Drawbacks: This method is only applicable for learning semi-structured texts. I don’t have any experience with it for memorizing formulas or entire books or learning to program. And it takes some time for the repeated write-off phases (but the pro is that you can do it regardless of your mental constitution or fitness).

A short example

Because the above steps could be somehow abstract for you, I’ll show you how I use the method in real life. I’m currently preparing a talk about legacy system reengineering and I have some learning matter I want to learn by heart. Imaging I would learn the subject in class. Here is what it would look like:

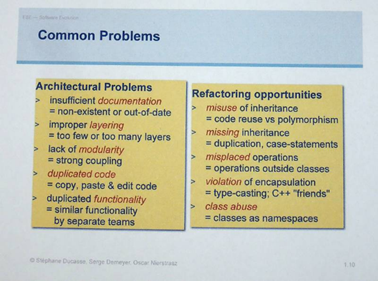

In class, the professor went very detailed through the following slide. I listen carefully to get an understanding, where the main point of interests are (Step 1: Listen):

The original slide

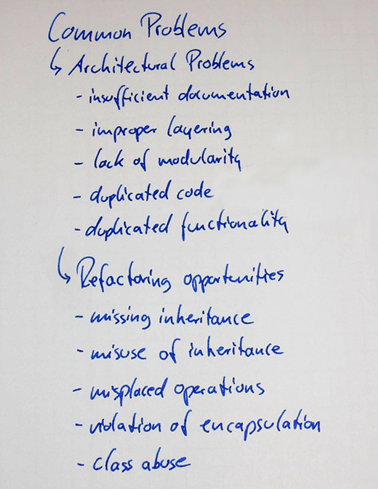

Just before the exam time, I read the slide a second time (Step 2: Read). Through the professor’s personal homepage I know that he is very interested in programming in general. So the most important points in the slide above are relevant for learning because they seem important to him (Step 3: Excerpt). But I can easily cut down some unnecessary information (all the stuff after the “=”), because, with my basic understanding of the learning matter, I don’t need that information. Next, I remove any styling or layout that isn’t necessary. For the slide above, I don’t need the two-column layout, so I remove it by simply writing everything in one column. After a minor reordering of some bullet points (which seems more logical to me), we write the remaining parts off by hand (I made a small error here, but I’ll show you afterward):

Normalized and linearized learning matter

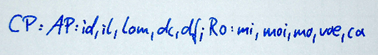

With the previous steps, we removed 100% distraction (fancy colors or weird layouts) and around 50% of the content. I now start to write off the above list at least three times before going to the next step (Step 6. Abbreviate). Because after the brainless activity of rewriting, I can now write down only every initial letter from the list. This looks like this (syntax explained later):

The complete slide as acronyms

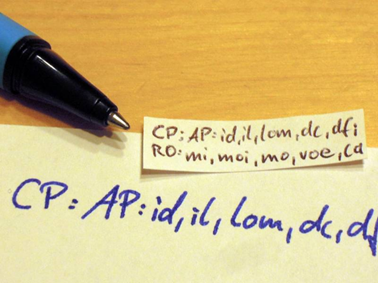

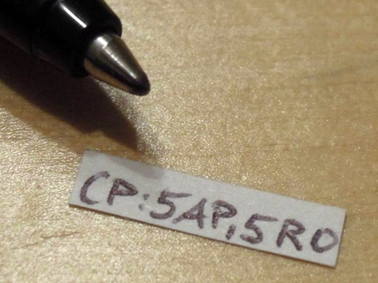

I repeat this at least seven times (Step 7: Repeat). Every time I write one of the initial letters, I expand the acronyms in my mind. For usability reasons, we create another little piece of paper with the content:

The “take away” version

You can go even further. If you already know the acronyms of the bullet points by heart, you can only write down the number of bullet points. But to get that working, you’ll need an additional learning technique like the method of loci or freaked out memory images (worth another blog post 😉 ).

Very minimalistic version

And overcome the temptation to use that for cheating ;-).

The Steps in detail

1. Listen

The first step is to listen very carefully in class. Concentrate 100% on the topic and don’t let disturb you from anyone. Think about it: You’re spending that time in class voluntarily. Use your precious time to do what you’re supposed to do: paying attention! In this step, you need to get a first feeling for the learning matter. You need to know what’s important and what isn’t. To gain this knowledge, we start at the person that created all the stuff you need to learn right now: The professor. It’s crucial to know that every person in the world lives in his or her world of perception. If the professor is an expert in programming, he won’t ask questions about economics in detail. If a professor is preparing a talk in the area of the learning subject, it’s most likely that he also get into detail in the exam. Especially pay attention to the stuff the professor added recently. This information is to some extent still present in his memory (see availability heuristic for more detail).

2. Read

In this step (that takes usually place before the last lesson of a class) you read through all the learning matter to get even a better feeling of the learning matter. In this step, you also identify anything that is unclear and prepare questions for the last session (because there is usually plenty of time for questions). Especially pay attention to any hint of the professor in the last lecture. Reading is an easy activity and gives you a good overview very quickly. A neat side effect is that you’re collecting and sorting all the relevant matter of the course: non-filed notes, scattered copies of relevant papers, missing printouts and so on. But everything into a nice file or place for later.

3. Excerpt

In this step, we extract the essence out of the learning matter. This would usually happen two weeks to one week before the exam. It highly depends on your starting material: If you have to learn from books, it will be a lengthier act, because you have to find the key messages and write them on paper. If you have some PowerPoint slides with some bullet points on it, you’ll be able to extract the relevant information faster.

But what is important? First, you have already a feeling for it, because you listened carefully in class and did some research on the professor’s biography. Second, there are almost always some archived exams available. Search for patterns or reoccurring questions in them. They are likely to be repeated. Third, be your professor! Imagine you have to write the exam. Which questions would be great to ask this time? If you can’t decide what is important, start to reduce the words by removing all the unnecessary ones (like “very”) or unnecessary long phrases (the “Bla Bla Bla” of the material).

Your goal should always be to know only for 80% of the learning material. That means you surely get a good note, if not the best one. If you are a gambler, you can also bet that some areas of your learning material won’t be part of the exam and thus you leave it out altogether. These two approaches take the strain out of the learning phase. The result of this step should be a collection of sheets of the relevant learning stuff on it (in the best case: bullet points).

4. Normalize

In this step, you remove any disturbance from the text by unifying everything to a single writing and layout style: It could be little things like bullet points where first words sometimes start with an upper case letter and sometimes with a lower case. Or non-uniform sentence structure (use of verbs vs. nominalization). Use the simplest way to formulate the content and keep it consistent.

Also remove fancy colors or weird layouts: Anything that can distract your brain. I like to have my learning material just on a nice blank sheet of paper, written down with a type of pen I can write very fast (I like the Schneider Slider Memo XB pens).

5. Write off

So here comes the first hard physical hard work: You’ll write everything you extracted and normalized off a few times (the number of iterations depends on the difficulty of your learning material). It is crucial that you concentrate entirely on the learning subject. It’s also the haptic feeling of writing that I like and that supports memorizing things. If you don’t want to write-off by hand, you can also typewrite the content.

6. Abbreviate

You’re almost there. Remember why we did all the previous steps? For two reasons: Reducing the substantial amount of learning matter and engaging all the time with the things we need to memorize. Now we prepare for memorizing all the learning subject by heart.

For writing with the least amount of distraction, I use the following syntax for structuring my content:

: -> level down: used for hierarchical bullet points to go one level deeper

; -> level up: used for hierarchical bullet points to go one level up

, -> separator: used for signaling another bullet point

| -> next topic: used to mark the beginning of another subject/slide

So if I’ve got to some bullet points like the following (in the example above, I haven’t paid attention to the different initial letters of the bullet points. They have to be in the same style):

-

Common Problems

-

Architectural Problems

- Insufficient Documentation

- Improper Layering

-

Refactoring Opportunities

- Missing Inheritance

- Misuse of Inheritance

-

This is what the abbreviated and structured version would be like (I just took the initial letters):

-

CP

-

AP

- ID

- IL

-

RO

- MI

- MoI

-

With the structure above, you can’t memorize the letters, so we linearize the content with the syntax I described above:

CP: (one level down in the bullet points’ hierarchy)

AP: (another level down in the hierarchy)

ID, (separation between the bullet points)

IL; (one level up)

RO: (one level down)

MI, (separator for another bullet point)

MoI

Or for short:

CP:AP:ID,IL;RO:MI,MoI

So we reduce 144 letters to 12 letter, which is 12x lesser content to write down physically.

Be free to add your characters or tricks for even more useful abbreviations!

7. Learn by heart

In this step, you repeat the acronyms. I like to write out the existing acronyms on paper just because I like that brainless activity. While writing the letters down, I decrypt the letters in my mind into the complete sentences. So I recall all the learning matter very quickly. I repeat this like ten times (because the challenge is fun). And that’s it!

A real life example

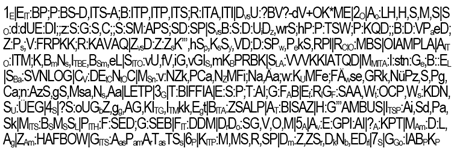

Here is what Extreme Reduction looks like for a real example. This is my abbreviated version of the course “Strategic IT Management.” 213 slides reduced to 749 characters (that’s six tweets!):

213 slides dumped into six tweets

I also used subscript and other symbols to improve the density even more. You can see some numbers that mark the chapters. In this exam, I almost got everything right (= best exam result). My professor was astonished :-).

Summary

Extreme Reduction is an easy method to get you to play with the learning matter. It not super sophisticated or complex. It’s just there to support you to learn by heart. Three years later I’m still impressed by the effectiveness of this method. And at one point I’m still surprised: The Extreme Reduction techniques don’t only support “cramming” or “bulimic learning” because I still know some of the abbreviations I’ve created three years ago and can even still decode their acronyms.

I wish you much fun while trying out that method and good luck with your exams! I would love to hear what you think about this approach, too!