Some months ago, I did some redocumentation work of a mid-sized legacy system (~1 Mio. LOC). Among other things, the system lacked consistency because there were many terms that were differently interpreted from different teams over the time. E. g. there were at least three different usages of the name “model” in class names: UI Model, Data Transfer Model, Database Model.

It’s hard to understand such a software system when there is so much ambiguity in naming. It really overloads your brain to quickly grasp the main ideas of such a system. But unfortunately, you can’t change such an old system as you like immediately. What I did instead was to document that developers should be cautious when they come to a class with “model” in its name. But just writing down the characteristics of those different models wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to show developers directly in the documentation how those different types of models could be identified and which they were. So I created a Code Inventory.

I want to show you the basic ideas and how you can do it yourself. But first, let’s define the term “Code Inventory”:

A Code Inventory is a listing of the concepts your software system is made of.

In a Code Inventory, you can list all kinds of concepts: Your controllers, your REST resources or your Data Access Objects – anything that you can systematically identify by syntax or structure. A Code Inventory helps you to keep track of the things that are already implemented in the software. Further, you can document all the little shortcomings that you plan to improve in the future – a great way to manage technical debt!

How can you build a Code Inventory? In reality, you create an inventory by counting the different items on the shelf. In virtuality, you count the items in your source code that represent the concepts.

Here the nice thing: For Java software systems, you don’t need to manually count your source code items that belong to a concept anymore. There is this nice static analysis tool jQAssistant that can do it for you. Just tell it what to find in your code by describing the concepts and it will give you the answer! jQAssistant scans your complete code base, stores a big graph of it in the graph database Neo4j. The graph of your software can then be queried by using the intuitively-to-use Cypher query language.

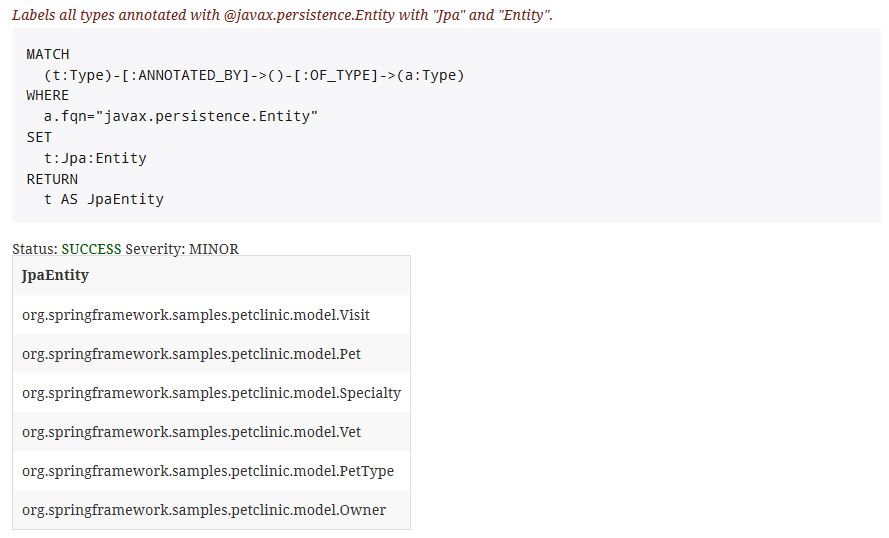

So for example, if I want to inventory the concept of JPA Entities (kind of Java’s database objects) in my application (e. g. in the Spring PetClinic project), I can create a query like this:

MATCH

(t:Type)-[:ANNOTATED_BY]->()-[:OF_TYPE]->(a:Type)

WHERE

a.fqn="javax.persistence.Entity"

SET

t:Jpa:Entity

RETURN

t AS JpaEntity

This will mark and list all the JPA Entites that exist in the source code:

| JpaEntity |

|---|

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.Visit |

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.Pet |

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.Specialty |

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.Vet |

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.PetType |

| org.springframework.samples.petclinic.model.Owner |

Because I also want to document that I have those Entities already, I can save that query in my documentation – a plain AsciiDoc file. jQAssistant will then execute this query on every build of my software system and I can find the query’s results in a separate report.

Here is another nice thing: Since a few days, jQAssistant will create an HTML documentation out of the AsciiDoc file including the query’s result!

This enables you to show readers of your documentation not only the concepts or characteristics of your code items but also where to find them directly in the documentation as well!

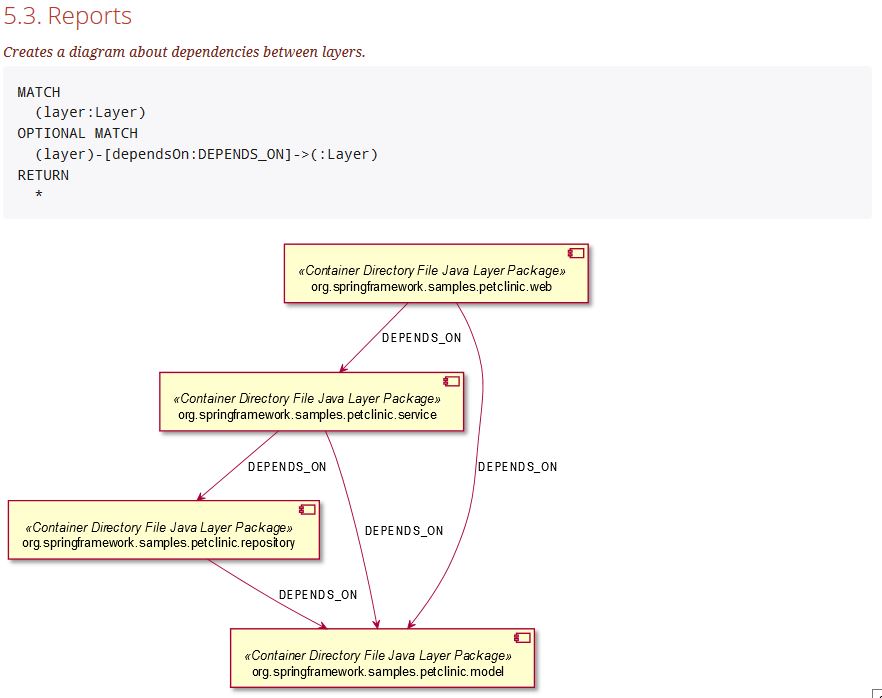

And here is another one of the newest things: jQAssistant can even create diagrams based on the query’s result, too, using PlantUML / GraphViz:

No more time wasted creating out-of-date UML diagrams. jQAssistant creates them directly from your code using the query you use in your documentation. This new feature connects documentation and code bidirectional.

With jQAssistant, you can now create a Code Inventory of your software system automatically. The documentation gets never out of date because the actual code is in your documentation.

T-H-I-S I-S S-O A-W-E-S-O-M-E !-!-!

If you find that, too, take a look at the complete example report or the excellent documentation to get a first impression of what jQAssistant is capable of!

PS: Thanks Dirk! That’s really a great addition to jQAssistant!

What do you think about this question I wrote today to JetBrains?

Is there any specialized DBMS exists specially tailored for storing object graphs? I’m asking this taking in mind the problem of legacy code analysis and refactoring (preferable with non-mainstream languages like embedded C dialects, old FoxPro apps, Delphi, SAP hell, GNU toolchain for Linux kernel and apps).

When fighting with someone else’s code, I periodically want to parse something (tiny firmware, or such big as the Linux kernel source code) and put it into such a database in the form of an attributed AST. So later I want to be able to run queries, transformations, and visualization on this object graph.

I tried neo4j and did not like the fact that it doesn’t have built-in tools to work separately with a group of ordered edges. For example, the 2+3 expression will be parsed into a b-tree with L/R edges, and you need to distinguish between these edges and other attributes in the queries (which will appear when types are displayed, or calculating the value).

This problem is more noticeable if you represent the array as an object, it has a set of attributes and separated set of ordered references to array members. If I write it in Python, it can be represented that I need a DBMS which has rich pattern matching support over the graph formed by the instances of the heirs of this class:

class Object:

val = ‘name’ # optional scalar value: object name, string / number

attr = {} # named attributes

nest = [] # ordered set

As far as I understand the problem: It’s a problem of order, isn’t it? You could use the nodes’s ids that signal this order, but I feel this isn’t what you want (or this would lead to complicated queries). In this case, I think there is an abstraction or a concept missing. How about adding some additional virtual relationship between the ordered edges, that signal the order? How about adding another label, that indicate the edges? In general, I didn’t run into this problem yet, because my “order” was always a nicely directed (sub-)graph. And I’m also on a higher abstraction level (structural information) like “classes that contain methods”.